Numerical methods

One

distinguishing component of the present SciDAC project is the

assessment and development of numerical methods suitable for problems

with interactions between turbulence, shock waves, and material

interfaces. Computational turbulence is a field where the subtle

details of the numerical method can have a dramatic impact on the

accuracy of the results -- one may even draw the wrong scientific

conclusions if one is not careful. The literature is filled with

numerical methods that perform well on shock waves or turbulence in

isolation, but much less is known about how these methods treat shocks

and turbulence simultaneously.

The

computational challenge of predicting shock/turbulence interactions

stems from the fundamentally different physics at play. Shock waves

are thin regions wherein flow properties change rapidly over a

distance roughly equal to the molecular mean free path; hence, they

are essentially strong discontinuities in the flow field. Turbulence,

on the other hand, is a chaotic phenomenon with broadband spatial and

temporal scales of motion. Most shock-capturing methods rely on strong

numerical dissipation to artificially smooth the discontinuity, such

that it can be resolved on the computational grid. However, the

artificial dissipation necessary for capturing shocks has a

deleterious effect on turbulence. An additional problem is the fact

that shock-capturing schemes are typically based on one-dimensional

Riemann solutions that are not strictly valid in multiple dimensions.

This can lead to anisotropy errors and grid-seeded perturbations.

Other complications arising from upwinding, flux limiting, operator

splitting, etc..., can seriously degrade performance and generate

significant errors.

The first

milestone of the present project is a comparison between a

set of promising methods on a carefully chosen suite of benchmark

problems. We have divided this item into two sub-items, by first

considering single-fluid cases only. The chosen

single-fluid problems represent the key physics with increasing

complexity:

1. Taylor-Green vortex: tests the accuracy and numerical stability on

broadband turbulence without shocks.

2. Spherical Noh implosion: tests the capability to achieve full shock

compression, correctly predict the shock speed, and maintain spherical

symmetry on an infinite Mach number shock without turbulence.

3. 1D Shu-Osher problem: tests the capability of predicting a

shock/entropy interaction, specifically to avoid damping of the

post-shock entropy fluctuations.

4. 2D shock/entropy/vorticity interaction: extends the 1D Shu-Osher

problem to two dimensions, with the associated induced unsteady

shock-movement.

5. High-Mach number decaying turbulence problem: includes broadband

vortical, acoustic, and entropy motions, as well as turbulence-induced

weak shocks.

We point out

that this benchmark study was undertaken in the spirit

of learning about the strengths and weaknesses of different

numerical approaches, with the obvious hope of devising future

improvements. Therefore all problems were computed by four different

numerical methods (i.e., codes) without ad hoc "tuning" for

each problem. It is important to realize that most methods can be "tuned" to give accurate results for the first four benchmark problems

-- but in the process sacrificing accuracy (or even stability) on

the remaining problems. No such tuning was performed here.

The four codes all represent different computational approaches, but

every one could be considered state-of-the-art within its context. A

brief summary of each code is given here:

1. The Miranda code (Cook, Phys. Fluids 2007}) uses very

high-order operators (8th-10th order) to approximate the

Navier-Stokes equations, with augmented artificial fluid

properties (like viscosity) to capture shocks and other

discontinuities. The guiding philosophy behind this method is to

first regularize the equations (through the artificial properties)

and then to solve the regularized equations using a very

high-order method. The code has been run on up to 65,536

processors on the BlueGene/L machine.

2. The Hybrid code (Larsson et al., CTR Annual Research Briefs

2007)

is based on the guiding idea that turbulence and shock waves are

fundamentally different phenomena and thus should be treated by

different numerical methods. Hence the Hybrid method relies

on a sensor to identify regions of shock waves, and then applies a

shock-capturing (WENO) scheme in these regions with a high-order central

difference scheme elsewhere. This hybridization ensures minimal

numerical dissipation in the method. The code has been run on up

to 4,096 processors on the Franklin Cray XT-4 machine.

3. The ADPDIS3D code (Yee and Sjogreen, J. Comput. Phys. 2007)

combines the best of non-dissipative high order spatial schemes with

shock-capturing methods via an efficient containment of numerical

dissipation. These low dissipative high order methods include limiting

and filtering with flow sensors. Flow sensors are used as an adaptive

procedure to analyze the computed flow data and indicate the amount,

location and type (e.g., spectral filter, compact filter or nonlinear

(shock) filter) of built-in numerical dissipation that can be

eliminated or further reduced. Such a filter method consists of two

steps, a full time step using a spatially high order non-dissipative

base scheme, followed by an adaptive multistep filter consisting of

the products of wavelet-based flow sensors and linear and nonlinear

numerical dissipations. The idea to control numerical dissipation is

very general and can be used in conjunction with high order spectral,

spectral element, finite volume and finite difference compact or

non-compact central spatial base schemes. Any shock-capturing scheme

can be used as nonlinear dissipation, (e.g., the dissipative portion

of the TVD, MUSCL, or (W)ENO methods), usually with flux limiters. The

linear filter can be the standard spectral or compact filter, or the

product of a high-order linear dissipation and an appropriate flow

sensor. By design, the flow sensors, spatial base schemes, and linear

and nonlinear dissipation models are stand-alone modules. Therefore, a

whole class of low dissipative high-order filter schemes can be easily

derived. With this family of adaptive filter schemes, a wide spectrum

of flow regimes can be simulated using the same code. Central spatial

base schemes of order up to 14 and the dissipative portion of

shock-capturing schemes of order up to 9 have been implemented.

4. The final code differs from the others by using shock-fitting,

rather than shock-capturing, to handle the shock waves.

In other words, the exact shock-jump relations are imposed at the

shock, which is therefore treated exactly.

The method yields superior accuracy for geometrically simple shocks,

but has yet to be applied to truly complex shock-structures.

|

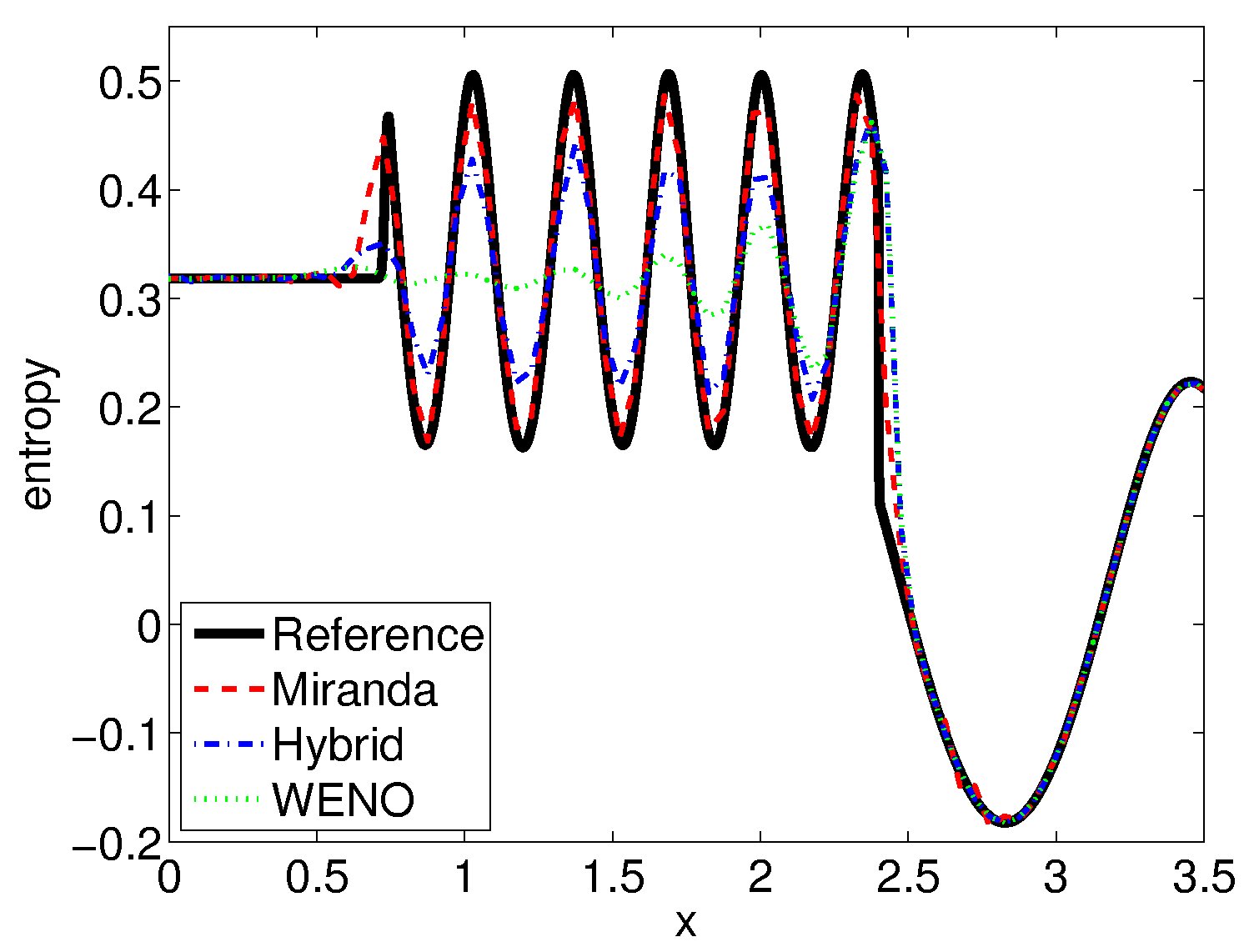

Figure 1. Entropy profiles after

shock-turbulence interaction. Results show that: 1) the Miranda

code performs extremely well on density disturbances; 2) standard

WENO is highly dissipative, which kills the entropy fluctuation;

3) the Hybrid approach significantly improves on this, despite

using the identical WENO scheme a the shock. |

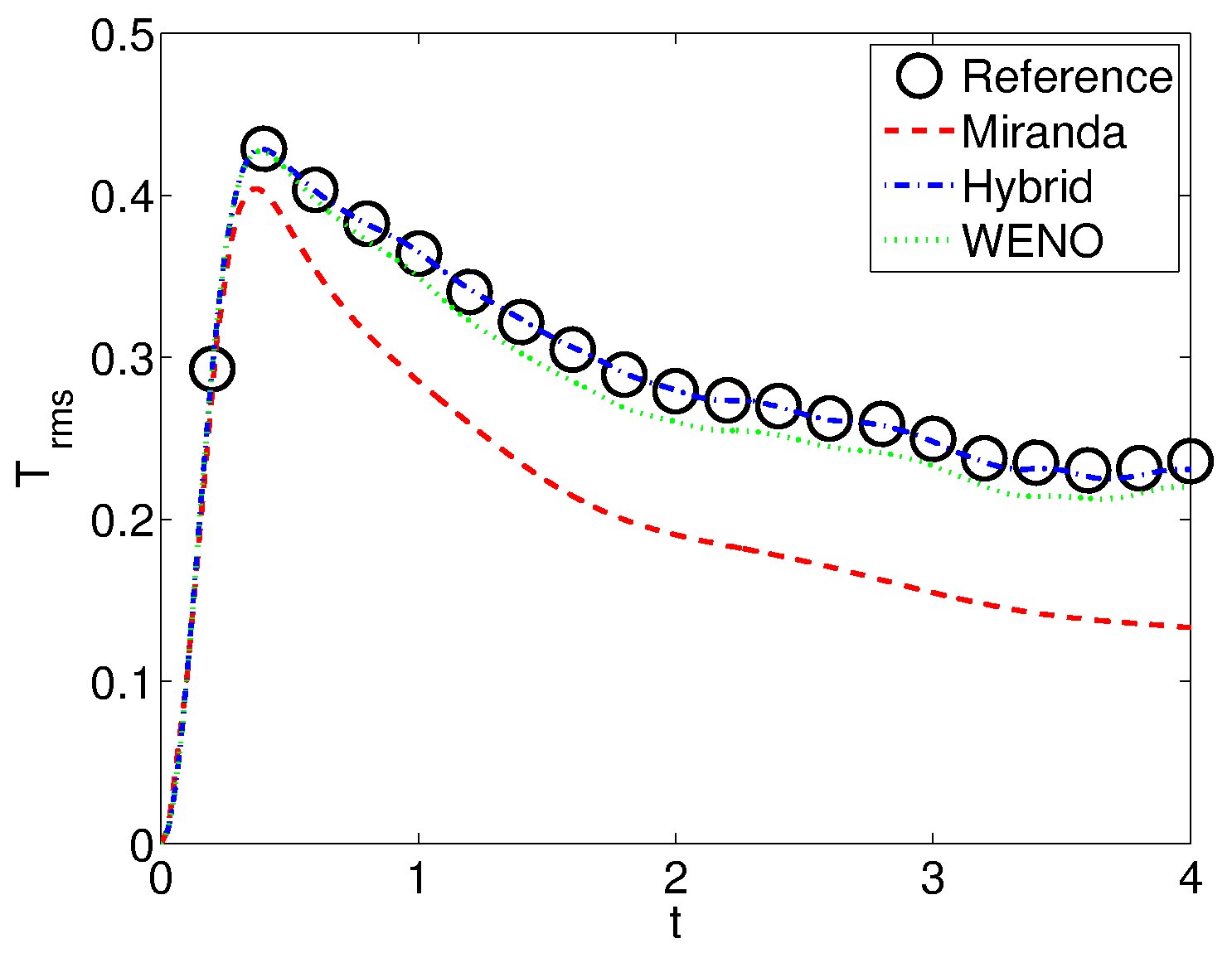

Figure 2. Temperature rms-profiles in

decaying isotropic turbulence. Results show that: 1) The Miranda

code excessively damps thermodynamic fluctuations; 2) standard

WENO and the Hybrid method are less dissipative. |

The benchmark comparison has brought several points to the

surface. Most important is that the comprehensive nature of the

problem suite has unmercifully brought out some of the weaknesses in

every method, and one could argue that some of these findings were

made possible only through the comprehensive suite. Figure 1 shows the profiles of entropy

after the shock-interaction in the Shu-Osher problem. The standard

WENO method is severely dissipative, and the Hybrid

philosophy of minimizing the dissipation by switching schemes is a

vast improvement. The Miranda method is highly accurate for

this problem, being capable of essentially capturing the full

entropy fluctuation even on this coarse (200 points) grid.

Figure 2 shows the evolution of

temperature fluctuations in decaying isotropic turbulence on coarse

(64^3) grids. Here the results are the opposite: this shows how

the behavior of numerical methods on computational turbulence with

shock waves is complex. The under-prediction by the Miranda

method is most likely caused by the artificial bulk viscosity;

improvements to the method that alleviate this issue have been and

continue to be investigated.

In addition to the sample giving above, some other findings from the

comprehensive assessment include:

1. While high-order WENO schemes are state-of-the-art in terms of

handling pure shock waves, they add significant numerical

dissipation on broadband turbulence and decrease the well-resolved

range of scales by a factor of two or more.

2. The solution-adaptive philosophy in the Hybrid method

drastically reduces the numerical dissipation, leading to much

more accurate treatment of broadband turbulence.

3. More work is needed on reliable shock sensors, that work in a

broad range of problems.

4. The Miranda treatment of shocks through artificial

fluid properties works well on well-resolved motions, but needs

improvement on broadband turbulence.